There is a notable parallel to the contemporary prophets of the Old Testament, one major difference being that Heraclitus' focus is the cosmos, rather than the creator. His words resemble those of a prophet, rather than those of a philosopher. Much of his appeal comes from the immediacy of his pre-conceptual or proto-conceptual statements. As with other pre-Socratics, his writings only survived in fragments quoted by other authors.

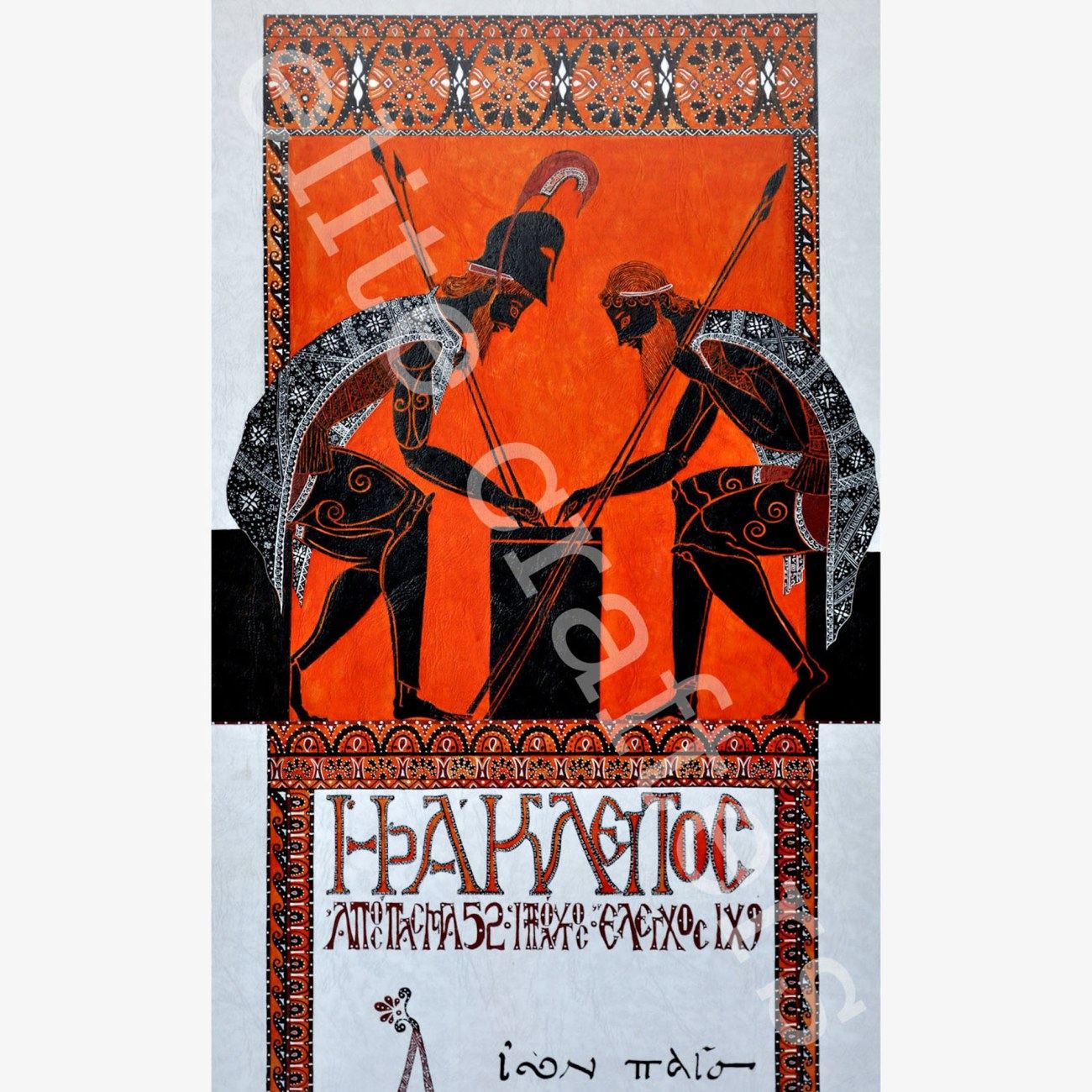

#Heraclitus fragments meaning full#

Although some subsequent thinkers attributed the full concept of dialectic to Heraclitus, much of his concept is unknown. Born in Ephesus, Asia Minor, he is known as the predecessor of the idea of dialectical movement, which identified the principle of change and progress with struggles. 535 – 475 B.C.E.) is one of the most important pre-Socratic philosophers. The Peripatetic Theophrastus diagnoses Heraclitus as "melancholic," based.The Greek philosopher Heraclitus (Greek Ἡράκλειτος Herakleitos) (c. The meaning and purpose of Heraclitus' book has always been found problematic, even by those who read it in its entirety. (B118)Ĭorpses should be thrown out quicker than dung.

(B25)Ī gleam of light is the dry soul, wisest and best. Greater deaths are allotted greater destinies. Others seem intended as pungently memorable aphorisms. Into the same rivers we step and do not step, we are and we are not. : living and dead, and the waking and the sleeping, and young and old. Many statements incorporate paradoxes or hover teasingly on the brink of self-contradiction. Heraclitus' carefully stylized and artfully varied Ionic prose ranges from plain statements in ordinary language to oracular utterances with poetical effects in vocabulary, rhythm, and word arrangement. The large number of extant fragments, however, offers little consolation to scholars bent on understanding his work. But unlike fellow Ionian philosophers-Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes-of whom virtually no writings survive, we have a significant number of fragments or close paraphrases from Heraclitus' book, On Nature. Unfortunately, little more is known about Heraclitus' obscure life. Historical accounts suggest, too, that he was a member of an Ephesian aristocratic family, but tradition tells us that he shunned the political life usually associated with such an upbringing, resigning a hereditary ruling position to his brother. Thus, if my analysis is correct, Homer's inability to solve the riddle stems not from foolishness, but from a confused understanding of logos.ĭoxographical reports show that Heraclitus was born in Ephesus, an Ionic city on the coast of Asia Minor, north of Miletus, and became influential about 500 B.C. If so, the solution should be regarded as an allegory of Heraclitean logos, common to all, yet strange and elusive to anyone seeking it.

If it can be shown that solving the lice-riddle requires an understanding of logos, the solution, on Heraclitus' account, would rest in something hidden and paradoxical. Fragments reveal that Heraclitus regards logos as something hidden and paradoxical.

Passages from ancient texts suggest that Homer identifies logos with superficial and conventional aspects of natural language. The reading I defend takes the fragment to be a critique of Homer's characterization of logos. I evaluate the plausibility of this reading and propose another, one having more philosophical relevance. Thus read, the fragment constitutes a puerile attack against Homer's character. Scholars suggest that Heraclitus intends to ridicule Homer's folly. The meaning of the fragment is both misleading and obscure. Men are deceived in the recognition of what is obvious, like Homer, who was the wisest of all the Greeks for he was deceived by boys killing lice, who said, "What we see and catch we leave behind what we neither see nor catch, we carry away. In fragment B56, Heraclitus recounts a traditional riddle and considers its significance:

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)